Among friends and family of those who die by suicide, a common refrain is: “I didn’t know.” While some individuals who die by suicide have prior attempts, about half have no documented suicidal thoughts or behaviors, nor do they have known psychiatric conditions like depression. They exhibit no previous clear indicators that they might be at risk.

A groundbreaking genetic study at the University of Utah has found that people in this group of unexpected suicides are not merely slipping through the cracks of psychiatric services. Their underlying risk factors may be fundamentally different. According to the research, individuals who die by suicide without prior non-fatal suicidal thoughts or behaviors have fewer psychiatric diagnoses and fewer underlying genetic risk factors for psychiatric conditions compared to those who had shown warning signs before dying by suicide.

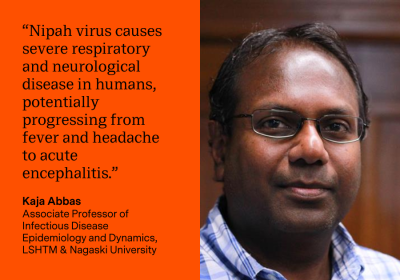

“There are a lot of people out there who may be at risk of suicide where it’s not just that you’ve missed that they’re depressed, it’s likely that they’re in fact actually not depressed,” says Hilary Coon, PhD, professor of psychiatry at the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine, University of Utah, and first author of the study. “That is important in widening our view of who may be at risk. We need to start to think about aspects leading to risk in different ways.”

Uncovering Hidden Risks

The results, published in JAMA Network Open, challenge conventional beliefs about suicide risk and suggest new approaches to help save lives. Previous research indicated that people who die by suicide without prior known suicidality are less likely to have psychiatric diagnoses, such as depression, compared to those with documented suicidal thoughts or behaviors. However, the root cause of this difference remained elusive.

Coon’s team discovered that this group has different genetic risk factors from people with known suicidality. By analyzing anonymized genetic data from over 2,700 people who died by suicide, the researchers found that those without prior suicidality tend to have fewer genetic risk factors for several psychiatric conditions, including major depressive disorder, anxiety, Alzheimer’s disease, and PTSD.

“A tenet in suicide prevention has been that we just need to screen people better for associated conditions like depression,” Coon explains. “And if people had the same sort of underlying vulnerabilities, then additional efforts in screening might be very helpful. But for those who actually have different underlying vulnerabilities, then increasing that screening might not help for them.”

Helping Those Most at Risk for Suicide

Figuring out how to identify and treat these “hidden” at-risk individuals is a major focus of Coon’s upcoming research. Previous studies with clinical data have shown potential links between suicide risk and hard-to-treat conditions like chronic pain. Coon is also investigating how other physical disorders, such as inflammation and respiratory conditions, may impact suicide risk. Her work will also focus on traits that may confer resilience to suicide.

Coon emphasizes that individual genetic risk factors related to suicide have very small effects on risk, and there’s no single gene—or combination of genes—that causes suicide. Environmental and societal contexts are crucial contributors to risk, and understanding the interplay between the environment and underlying biology will be essential to discovering who’s at risk.

“We hope our work will begin to define subsets of individuals at risk, and also the contexts in which these risk characteristics may be important,” Coon says. “If people have a certain type of clinical diagnosis that makes them particularly vulnerable within particular environmental contexts, they still may not ever say they’re suicidal. We hope our work may help reveal traits and contexts associated with high risk so that doctors can deliver care more effectively and specifically.”

Implications for Future Research and Prevention

The implications of this study are significant for future research and suicide prevention strategies. The findings suggest that traditional screening methods may not be sufficient for identifying all individuals at risk of suicide. Instead, a more nuanced approach that considers genetic and environmental factors is necessary.

As research continues, the hope is to better identify at-risk individuals and provide them with the care they need. This could lead to more personalized and effective interventions, ultimately reducing the incidence of suicide.

In conclusion, this study represents a paradigm shift in understanding suicide risk. By uncovering the hidden genetic factors and challenging existing prevention strategies, it opens new avenues for research and intervention, aiming to save lives and provide support to those who need it most.