In a nation once celebrated for its free university education, Australians now face staggering tuition fees, with arts degrees costing upwards of A$50,000. A recent YouGov survey conducted in June 2025 highlights growing discontent, with 47% of Australians believing that a worker on an average income should be able to pay off their student debt within five years. Furthermore, 58% argue that annual tuition should be A$5,000 or less, a stark contrast to current rates.

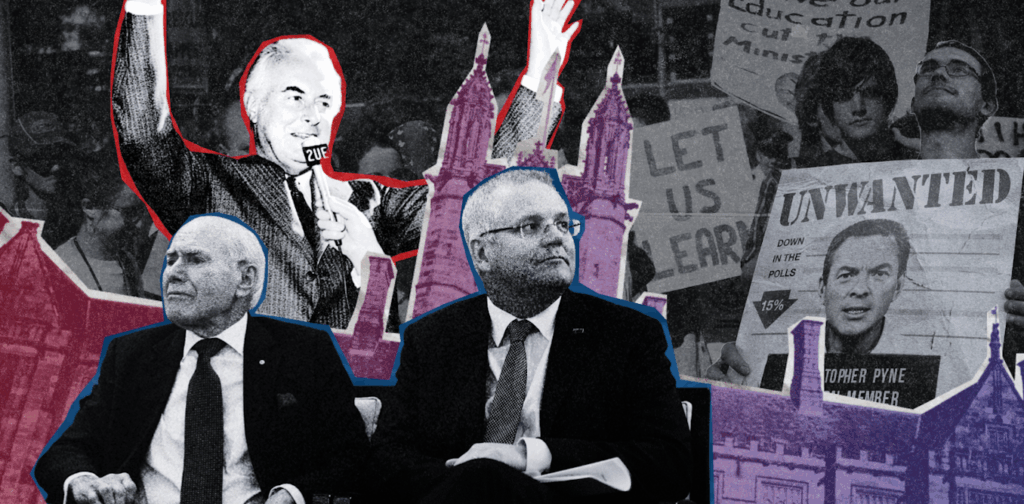

Reflecting on the past, 18% of respondents believe university education should revert to being free, as it was 50 years ago under the Whitlam Labor government. The introduction of the Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS) by the Hawke Labor government in 1989 marked the end of free education, setting a precedent for the evolving financial landscape of Australian universities.

The Journey from Free Education to HECS

The transformation of Australian universities can be traced through three distinct eras. Initially, the “sandstone era” from 1850 to 1945 saw each state establish its own university. This was followed by a period of expansion from 1945 to 1983, during which the Commonwealth assumed primary funding responsibilities while states managed governance. This era culminated in the 1974 reforms by Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, who declared, “We will abolish fees at universities and colleges of advanced education.”

However, the Whitlam reforms, while eliminating fees, did not address issues of access and equity due to limited university places. The subsequent Dawkins reforms of the 1980s, named after Education Minister John Dawkins, reshaped the higher education sector, introducing market-oriented policies and encouraging universities to operate like corporate entities.

The Dawkins Era and Internationalization

The Dawkins reforms expanded access to higher education, transforming colleges and institutes into universities. This expansion was coupled with a shift towards internationalization, as the Hawke government introduced full-fee-paying systems for international students. According to Andrew Norton of Monash Business School, this decision was pivotal, leading to double-digit growth in international enrolments throughout the 1990s.

By 2024, international students constituted 26% of total enrolments, and Australian universities excelled in global rankings, boasting nine institutions in the top 100 of the 2026 QS rankings. This international focus, however, prioritized research over student satisfaction, creating a cycle where universities relied on international fees to fund research, thereby boosting rankings and attracting more international students.

Government Policies and Rising Costs

The introduction of the Job Ready Graduates scheme in 2021 by the Morrison Coalition government marked another shift, disconnecting student fees from potential graduate earnings. This policy aimed to steer students towards fields with national labor shortages by manipulating tuition fees. However, it failed to alter student choices significantly, as evidenced by studies showing fewer than 1 in 50 students changed their field of study due to differential fees.

Despite these intentions, the policy exacerbated inequities, particularly for arts students who now face the highest fees despite lower graduate incomes. An arts degree now incurs a debt of A$50,976 over three years, compared to A$13,881 for degrees in agriculture or mathematics.

Pressures and the Call for Reform

The financial burden on students is compounded by rising living costs, forcing many to juggle full-time work with full-time study. As a result, the average time to repay student debt has increased to 9.9 years, with many graduates carrying debt into their thirties.

The Albanese Labor government’s decision to reduce student debt by 20% offered temporary relief but did not address the underlying issue of high fees. The Australian Universities Accord interim report in June 2023 emphasized the need to reform the Job Ready Graduates package to prevent long-term damage to the education system.

The call for a new funding model has been echoed by the Productivity Commission, which criticized the existing system’s design flaws. The Accord’s final report in February 2024 highlighted the need to replace the current fee structure to ensure fairness and sustainability.

As the government deliberates on these recommendations, the future of Australian higher education hangs in the balance, with students and educators alike awaiting decisive action to rectify a system that has drifted far from its egalitarian roots.