Increasing daily steps by even a small amount could significantly slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease in individuals at heightened risk, according to a groundbreaking study published in Nature Medicine. Conducted by researchers at Mass General Brigham, the study found that physical activity correlates with slower cognitive decline in older adults with elevated levels of amyloid-beta, a protein linked to Alzheimer’s.

The research revealed that cognitive decline was delayed by an average of three years in individuals who walked 3,000 to 5,000 steps daily. Those who managed 5,000 to 7,500 steps per day saw a delay of up to seven years. In stark contrast, sedentary individuals experienced a more rapid buildup of tau proteins in the brain, leading to faster declines in cognition and daily functioning.

Understanding the Impact of Lifestyle on Alzheimer’s Progression

“This sheds light on why some people who appear to be on an Alzheimer’s disease trajectory don’t decline as quickly as others,” stated Dr. Jasmeer Chhatwal, MD, PhD, senior author and neurologist at Mass General Brigham. “Lifestyle factors appear to impact the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting that lifestyle changes may slow the emergence of cognitive symptoms if we act early.”

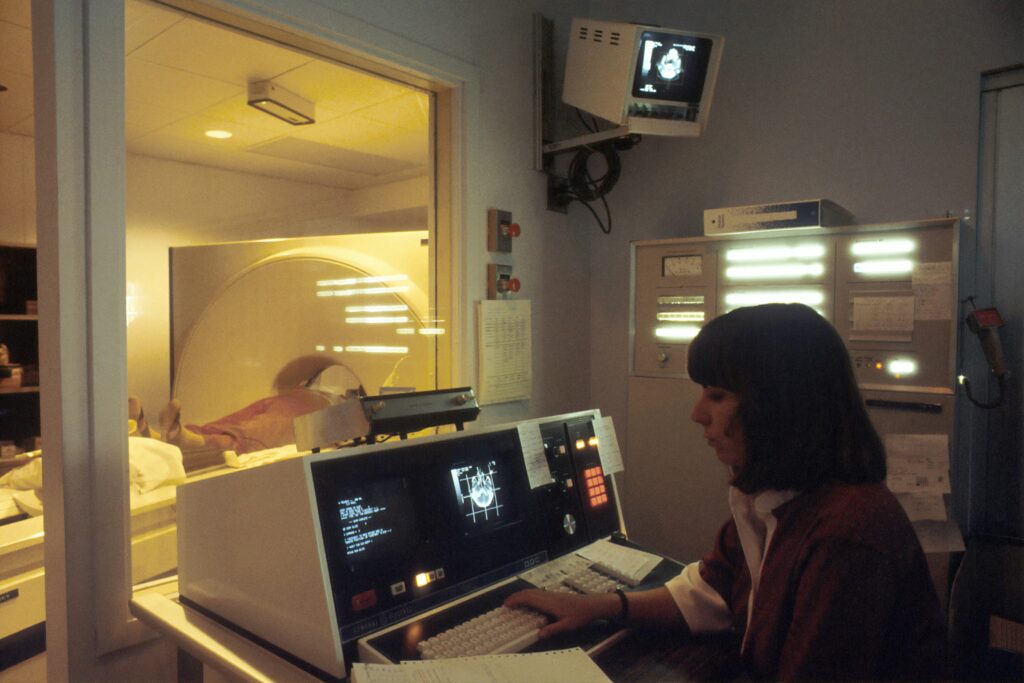

The study analyzed data from 296 participants aged 50 to 90 years old, all of whom were cognitively unimpaired at the study’s onset. Utilizing PET brain scans, researchers measured baseline levels of amyloid-beta and tau proteins. Participants’ physical activity was tracked using waistband pedometers, with annual cognitive assessments conducted over an average of 9.3 years. A subset of participants also underwent repeated PET scans to monitor tau changes.

Key Findings and Statistical Insights

Higher step counts were linked to slower rates of cognitive decline and a slower buildup of tau proteins in participants with elevated baseline levels of amyloid-beta. Researchers’ statistical modeling suggested that most benefits of physical activity in slowing cognitive decline were driven by slower tau buildup.

For those with low baseline levels of amyloid-beta, little cognitive decline or tau accumulation was observed over time, and no significant associations with physical activity were noted. Dr. Reisa Sperling, MD, co-author and neurologist at Mass General Brigham, emphasized the significance of these findings: “These findings show us that it’s possible to build cognitive resilience and resistance to tau pathology in the setting of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease.”

Future Directions and Implications for Alzheimer’s Prevention

Looking ahead, researchers plan to explore which aspects of physical activity are most beneficial, such as exercise intensity and long-term activity patterns. They also aim to investigate the biological mechanisms connecting physical activity, tau buildup, and cognitive health. This research could inform future clinical trials testing exercise interventions to slow cognitive decline, particularly in individuals at risk due to preclinical Alzheimer’s disease.

“We want to empower people to protect their brain and cognitive health by keeping physically active,” said first-author Dr. Wai-Ying Wendy Yau, MD. “Every step counts — and even small increases in daily activities can build over time to create sustained changes in habit and health.”

Contributors and Funding

The study was authored by a team from Mass General Brigham, including Dylan R. Kirn, Michael J. Properzi, Aaron P. Schultz, and others. The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, and the Massachusetts Life Sciences Center.

The findings, published under the title “Physical Activity as a Modifiable Risk Factor in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease,” underscore the potential of lifestyle interventions in delaying the onset of Alzheimer’s symptoms, offering hope for future prevention strategies.