A groundbreaking brain imaging study has revealed that men experience a slightly greater age-related decline in brain structure compared to women. This finding challenges the prevailing notion that brain aging patterns contribute to the higher prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in women. The research, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, offers new insights into the complex dynamics of brain aging.

Alzheimer’s disease, a progressive neurodegenerative condition, is the most common cause of dementia, with women accounting for a significant majority of cases globally. Given that advancing age is the most significant risk factor for developing Alzheimer’s, researchers have long speculated whether sex-based differences in brain aging might explain this disparity. However, the latest study suggests otherwise.

Research Methodology and Key Findings

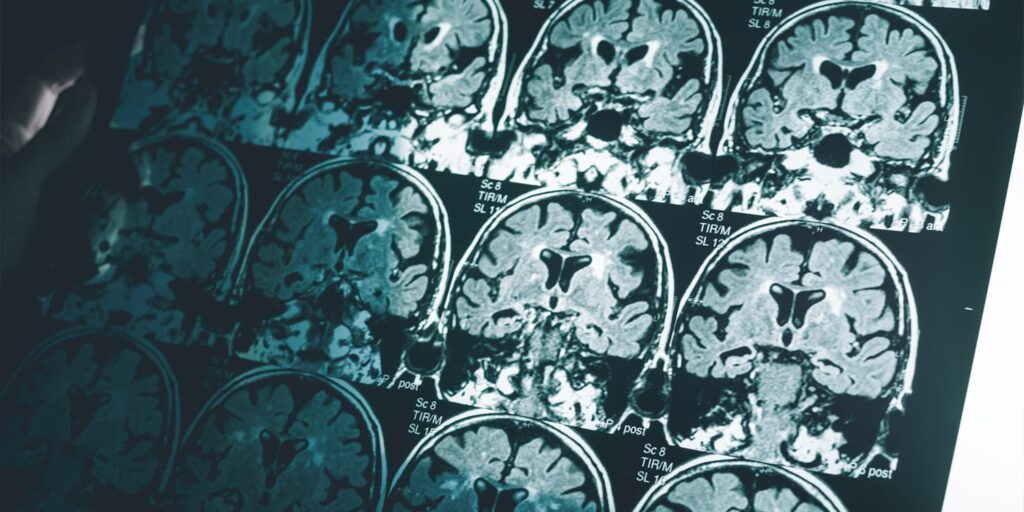

The study, conducted by an international team led by the University of Oslo, utilized an extensive dataset comprising 12,638 MRI scans from 4,726 cognitively healthy participants aged 17 to 95. The longitudinal nature of the data, with individuals scanned at least twice over an average interval of three years, allowed researchers to track brain changes over time.

Initial analyses revealed that men experienced a steeper decline than women in 17 different brain measures, including reductions in total brain volume, gray matter, and white matter. Men also exhibited faster thinning of the cortex in visual and memory-related areas. After adjusting for head size, the pattern largely persisted, with men showing a greater rate of decline in specific brain regions.

“Although earlier studies have shown mixed findings, especially for cortical regions, our results align with the overall pattern that men show slightly steeper age-related brain decline,” said Anne Ravndal, a PhD candidate at the University of Oslo and study author.

Age-Dependent Effects and Implications

The study also uncovered age-dependent effects, particularly in adults over 60. In this age group, men showed a more rapid decline in deep brain structures involved in motor control and reward, while women exhibited a greater rate of ventricular expansion.

Interestingly, after correcting for head size, no significant sex differences were found in the decline rate of the hippocampus, a critical structure for memory formation heavily affected by Alzheimer’s disease. This suggests that normal brain aging may not fully explain the higher incidence of Alzheimer’s in women.

“Our findings add support to the idea that normal brain aging doesn’t explain why women are more often diagnosed with Alzheimer’s,” Ravndal noted. “The results instead point toward other possible explanations, such as differences in longevity and survival bias, detection and diagnosis patterns, or biological factors.”

Challenges and Considerations

While the study provides valuable insights, it is not without limitations. The data were collected from multiple sites, which can introduce variability, and the follow-up intervals for brain scans were relatively short. Additionally, participants were all cognitively healthy, meaning the findings may not apply to changes occurring in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

The researchers also emphasized that the sex differences observed were modest. For instance, in the pericalcarine cortex, men showed an annual decline rate of 0.24% compared to 0.14% for women.

“The sex differences we found were few and small,” Ravndal told PsyPost. “Importantly, we found no evidence of greater decline in women that could help explain their higher Alzheimer’s disease prevalence.”

Future Directions and Research

Looking ahead, future research could explore factors like differences in longevity, potential biases in disease detection and diagnosis, or biological variables such as the APOE gene, a known genetic risk factor. The team is also investigating whether similar structural brain changes relate differently to memory function in men and women.

“We are now examining whether similar structural brain changes relate differently to memory function in men and women,” Ravndal said. “This could help reveal whether the same degree of brain change has different cognitive implications across sexes.”

The study’s findings underscore the complexity of brain aging and its implications for understanding Alzheimer’s disease, highlighting the need for further research to unravel the intricate mechanisms at play.