A fossil discovered over two decades ago on England’s Jurassic Coast has emerged as one of the most significant marine reptile findings in recent history. The nearly complete skeleton of a long-snouted ichthyosaur, now classified as Xiphodracon goldencapensis, or the “Sword Dragon of Dorset,” is helping scientists fill an evolutionary gap from the Early Jurassic era, approximately 193 to 184 million years ago.

Uncovering a Sea Dragon

The fossil was initially discovered in 2001 at Golden Cap, a cliff along the southwest coast of England, by local collector Chris Moore. It was subsequently relocated to the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada, where it remained largely intact until scientists from the University of Manchester and other institutions re-examined it.

Dr. Dean Lomax from the University of Manchester was among the first to recognize the fossil’s uniqueness during a 2016 review. “I knew it was abnormal at the time but did not anticipate that it would turn out so significant to filling a gap in what we know,” Lomax explained. The study concluded that it represented a new species.

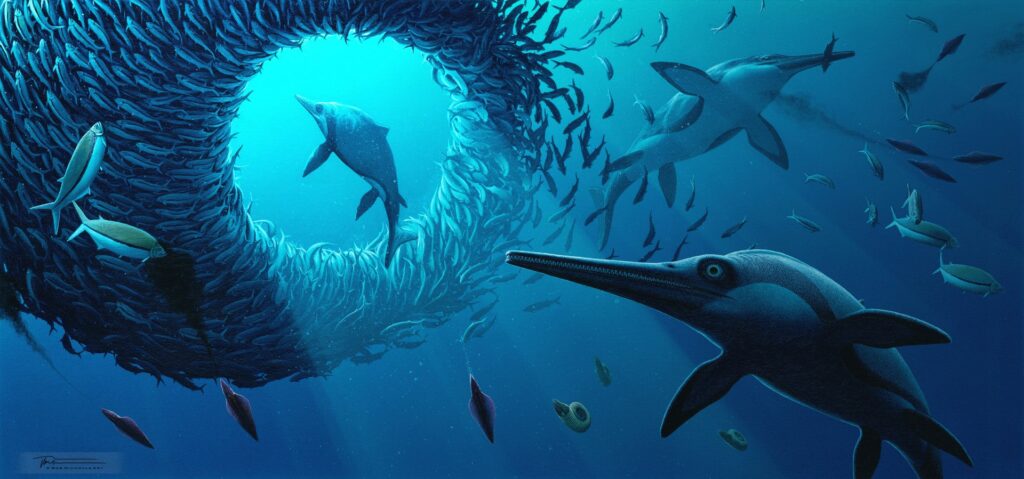

Measuring approximately three meters in length, Xiphodracon was comparable in size to a modern dolphin. It featured a massive eye socket and a wide, sword-like snout lined with sharp teeth, ideal for catching fish and squid in ancient oceans. Its name is derived from the Greek words xiphos (sword) and dracon (dragon), reflecting the “sea dragon” moniker ichthyosaurs have held for over 200 years.

A Window on a Lost World

The Early Jurassic Pliensbachian stage has long been a frustrating gap in the fossil record. While thousands of ichthyosaur skeletons have been found before and after this period, fossils from the Pliensbachian are rare, leaving scientists curious about the evolution of sea reptiles during this epoch.

Prior to the discovery of Xiphodracon, researchers noted significant differences between ichthyosaur genera before and after the Pliensbachian, despite occupying similar ecological niches. The new fossil suggests that this evolutionary “turnover” occurred earlier than previously believed, indicating stronger affinities to taxa of the later Toarcian age and extending the timeline for when newer ichthyosaur clades replaced older ones.

“This is a key time for the ichthyosaurs because a few of the families did become extinct and some new ones cropped up,” Lomax said. “But Xiphodracon is one that you can say is missing from the ichthyosaur jigsaw.”

Anatomy, Injuries, and Signs of a Struggle

The fossil is remarkably well-preserved, with nearly the entire skeleton intact and three-dimensional, unlike most flattened fossils. Exceptions include a single hind flipper and the tail tip. Researchers also found signs of trauma: tooth marks on the skull suggest the reptile was bitten by a larger predator, possibly another ichthyosaur. Some teeth and bones show signs of disease or stress, offering insights into the dangers of Jurassic oceans.

A particularly unusual feature caught scientists’ attention: a prong-like bony bump near the nostril, part of a bone called the lacrimal. No other ichthyosaur is known to possess such a feature. Its purpose remains a mystery, but it may have influenced breathing, streamlined swimming, or enhanced sensory perception, suggesting these animals were more anatomically diverse than previously thought.

Filling Evolution’s Gaps

Paleontologists refer to periods like these as “faunal turnover,” where old species die out and are replaced by new ones. Ichthyosaurs experienced such a shift during the Pliensbachian, but researchers couldn’t determine when the turnover began until now. Xiphodracon completes the missing record, indicating that the evolutionary change was gradual rather than abrupt.

As co-author Professor Judy Massare of the State University of New York puts it, “Thousands of complete or nearly complete ichthyosaur skeletons are known before and after the Pliensbachian. Something catastrophic happened to species diversity sometime during the Pliensbachian, that’s certain. Xiphodracon allows us to pinpoint when the change took place, but we still don’t know why.”

The “why” remains one of paleontology’s greatest questions. Climatic changes, sea temperature fluctuations, or competition for food might have been factors. Each new fossil discovery from this time has the potential to reveal more pieces of the puzzle.

The Long Journey to Discovery

Xiphodracon sat unrecognized in the Royal Ontario Museum collections for decades. Its importance became apparent only after new analytical techniques and comparisons highlighted its uniqueness. This tale underscores the value of museum archives, where even fossils stored for centuries can provide solutions to scientific puzzles.

The fossil will eventually be displayed at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, allowing the public to view what paleontologists are calling the most complete Pliensbachian marine reptile skeleton on Earth. It serves as evidence that the Jurassic Coast—already a global hotspot for fossils—still has many secrets left to uncover.

Questions Still Unanswered

Although Xiphodracon has provided insights into ichthyosaur evolution, much remains unknown. Why did it possess its unique pronglike snout bone? How common was the species—was it confined to the seas around England, or was its range more extensive? And why did the general change in ichthyosaur species during the Pliensbachian occur?

Scientists hope that continued fieldwork and further studies of fossilized creatures in museums will provide answers. Each new find can refine the timeline of how these rapid, dolphin-like reptiles developed and thrived in prehistoric oceans.

Practical Implications of the Research

This discovery not only rewrites the ichthyosaur family tree but also reshapes our understanding of how evolution unfolds in the sea. By placing Xiphodracon goldencapensis on the map as an early representative of subsequent ichthyosaur groups, researchers can more accurately reconstruct evolutionary leaps.

The research highlights the importance of maintaining museum collections and examining specimens, where overlooked fossils can still overturn our understanding. More broadly, it demonstrates that radical evolutionary transformations can occur slowly and unnoticed, rather than suddenly—a lesson applicable to the study of diversity and extinction in today’s rapidly changing marine ecosystems.

Research findings are available online in the journal Papers in Palaeontology.