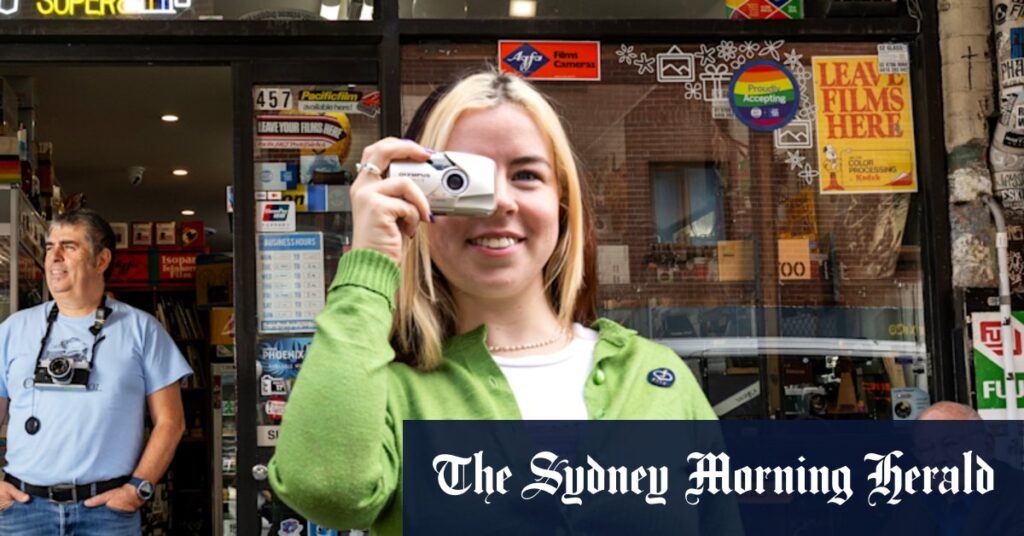

If Sydney Super8 had a shopkeeper’s doorbell on a Friday afternoon, it would be ringing constantly with the steady stream of young people coming and going. The old-school film and camera shop, nestled in Newtown, is considered an institution, with its bright Kodak-yellow exterior catching the eye of passing pedestrians.

Inside, the narrow shop space is often bustling with millennials and Gen Z customers. They drop off single-use cameras for processing, buy rolls of film from the fridge, or seek technical advice from current owner Nick Vlahadamis and former owner Christopher Tiffany. “Our customers are 90 percent young people, and maybe 75 percent of the time they are female,” says Tiffany. “You get half a dozen girls at the table outside going through their pictures, giggling, laughing, and carrying on like crazy.”

Vlahadamis notes that the store has attracted a younger crowd since it opened in its current location in 2013, with a noticeable increase post-pandemic. “Social media has an impact, it’s really weird, [that] digital social media has an impact on an old technology. I think the same thing happened with records,” he explains.

Gen Z’s Nostalgic Turn

The revival of film photography among younger generations is part of a broader cultural shift towards nostalgia. Twenty-six-year-old Lilly Orrell, a regular at Sydney Super8, exemplifies this trend. She shoots on film for fun and because it looks “cute,” using her camera to capture candid moments with friends and on holidays. “It captures the moment, you can’t be like ‘I look ugly’ and re-take it… The photo is what it is,” she says, reflecting on her break from Instagram due to the pressure of curating a ‘perfect’ image.

Orrell’s sentiments echo a wider movement among Gen Z, who are increasingly valuing authenticity over the polished veneer of digital media. “I look back through my parents’ pictures, and it’s all about the memory and not about performing. When I get to 60, I can look back at my film photos and reminisce,” she adds.

The Industry’s Response

This resurgence in analog photography comes at a crucial time for the industry. In August, Eastman Kodak reported significant debt in its quarterly filings, sparking rumors of potential closure. However, Kodak clarified that these reports were misleading, stating that it has “no plans to cease operations” and is “confident it will repay, extend, or refinance its debt.”

In a bid to meet the growing demand, Kodak temporarily paused its film production in November 2024 to upgrade its New York factory. Meanwhile, Japanese camera manufacturer Pentax launched the Pentax 17 last year, marking the first new film camera from a major brand since the early 2000s. “It’s a camera that shouldn’t exist today. They have almost sold out globally. But as a major manufacturer, Pentax has gone out on a limb,” says Vlahadamis.

Similarly, FujiFilm Australia re-launched its QuickSnap, a 35mm single-use camera, targeting Gen Z customers. “Gen Z are a lot about mental health, slowing things down, realising what we had in the past was great,” says Mary Georgievski, FujiFilm Australia’s general manager. “While they’re highly connected digitally, Gen Z is driving a renewed appreciation for analog, choosing film not in place of digital, but alongside it.”

The Allure of Analog

For many young people, the appeal of film photography lies in its authenticity and the element of surprise. Denis Hasagic, a 25-year-old regular at Sydney Super8, initially saved up for a digital camera but opted for his dad’s old Pentax MZ-50 instead. “Only four out of 37 photos turned out, but I was already hooked,” he recalls. “I saved up all this money for a digital camera and then got a film camera for much cheaper and spent the extra money on film and development.”

Hasagic appreciates the mindfulness that shooting on film requires, describing it as a process that forces one to slow down and embrace the unexpected. “There’s also the surprise element. When you get the scans back and the photo you thought was going to be really good turns out bad, but the photo you took accidentally is really amazing,” he says.

Professional photographer Julia Sarantis, 29, shares this sentiment. “Even though it’s heartbreaking, there are so many rolls [of film] that just didn’t turn out … but it’s magic when it happens,” she says. Sarantis discovered her passion for film photography during a university elective. “As soon as I got in the dark room and saw the magic of the development, I got hooked,” she explains. “I’ve always had an interest in old technology. But I think in a larger, cultural way it’s a deviation from the immediacy of digital technology.”

As the film photography revival continues, Vlahadamis hopes more young people will desire physical prints alongside digital scans, though he understands the allure of sharing images on social media. “You get one shot. We are in such an era right now where everything is instant … You’re going back to the future in a way,” he remarks.

With the renewed interest in analog photography, Sydney Super8 stands as a testament to the enduring charm of film, capturing the hearts of a new generation eager to embrace the imperfections and authenticity that digital technology often lacks.