Out-of-home care placements for children in Finland have doubled since 1993, according to a recent study published in the journal Child Abuse & Neglect. This significant increase highlights a growing trend in child welfare interventions, where children are removed from their homes due to various complex factors, including abuse, neglect, or mental health issues.

The research, conducted by Aapo Hiilamo and Mikko Myrskylä from the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (MPIDR) in collaboration with the University of Helsinki, utilized demographic methods to provide a comprehensive overview of the situation. Their findings reveal that traditional metrics may not fully capture the nuances of out-of-home care, prompting the need for more sophisticated analysis.

New Metrics for a Nuanced Understanding

Traditional approaches to monitoring out-of-home care often rely on static counts of children living outside their parental homes at specific times. However, Hiilamo argues that these figures can be misleading as they fail to consider age structure, care duration, stability, and family reunification possibilities.

“We aimed to address these challenges by measuring multiple aspects of out-of-home care simultaneously,” Hiilamo explains. The team tracked the daily living arrangements of all Finnish children from 1993 to 2020, calculating probabilities of entering and exiting care by age and year. This approach offers a more detailed picture of the child welfare landscape.

Rising Trends and Their Implications

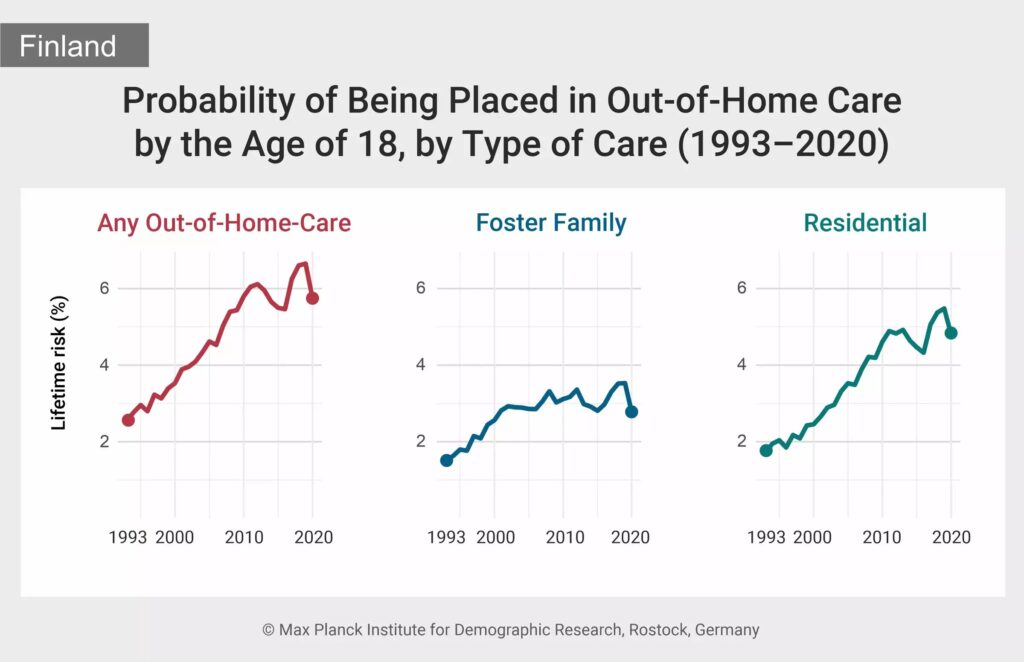

According to the study, approximately 6% of children in Finland are expected to experience out-of-home care at least once during their childhood under 2020 conditions—a twofold increase since 1993. This rise is primarily attributed to an increase in residential care placements, though foster family placements have also grown.

Despite the increased risk of placement, the expected duration of care has decreased from 4.2 years in the early 1990s to 3.5 years in 2020, with the probability of a sustained return home by age 18 rising from 32% to 44%.

“The rise in out-of-home care, particularly in residential settings, is both concerning and puzzling,” Hiilamo notes. He points out that known risk factors like juvenile delinquency and alcohol consumption have not seen parallel increases, nor are similar trends observed in other Nordic countries. This discrepancy calls for further investigation into Finland’s unique situation.

Demographic Methods: A New Frontier in Child Welfare Research

The study’s multistate models offer a novel approach to understanding child welfare dynamics and can be adapted for use in other countries and contexts. These models could help explore transitions between various child and youth welfare services or assess risks like running away from foster care.

“Demographic research often focuses on aging populations, but these methods are equally valuable for studying children and youth,” Hiilamo concludes. The new software developed at MPIDR makes these tools more accessible, potentially transforming how child welfare services are evaluated globally.

As Finland grapples with these rising trends, the study underscores the need for continued research and innovation in child welfare policy. Understanding the underlying causes and implications of increased out-of-home care is crucial for developing effective interventions and ensuring the well-being of vulnerable children.