Some of the first human settlers in the Americas carried more than primitive skills and tools; they also brought with them a small but powerful genetic variant known as MUC19. This gene fragment, inherited from an extinct hominin called Denisovans, appears to have played a crucial role in helping early humans adapt to new diseases, foods, and landscapes. A recent study led by the University of Colorado Boulder, with contributions from Brown University, has traced a Denisovan-derived variant of the MUC19 gene that is surprisingly prevalent among people with Indigenous American ancestry.

The announcement comes as scientists continue to unravel the complex web of human evolution. “In terms of evolution, this is an incredible leap,” said Fernando Villanea, an assistant professor in the Anthropology department at CU Boulder and a lead author of the study. “It shows an amount of adaptation and resilience within a population that is simply amazing.” This discovery ties a deep past event to a much later journey, illustrating how the Denisovan version of MUC19 made its way into some human populations through a series of interbreeding events.

Extinct Cousins and Their Genetic Legacy

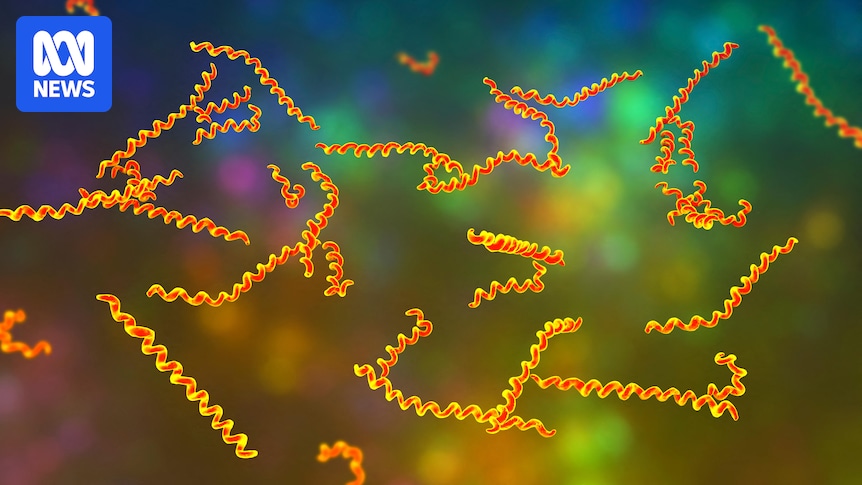

Denisovans, close cousins of both humans and Neanderthals, ranged from Siberia south toward Oceania and west onto the Tibetan Plateau. Despite the scarcity of fossil evidence, the first recognized Denisovan was identified only 15 years ago through DNA in a bone fragment. While physical characteristics remain largely speculative, their genetic legacy is well documented.

According to Villanea, “We know more about their genomes and how their body chemistry behaves than we do about what they looked like.” Denisovans left behind DNA in many modern people, influencing traits ranging from immunity to altitude tolerance. MUC19, part of a family of 22 mucin genes in mammals, helps build mucus, a frontline barrier that protects tissues and traps pathogens.

MUC19: A Genetic Advantage in the Americas

The study highlights how earlier work showed Denisovans carried a distinctive MUC19 sequence, which some modern humans inherited. While all modern humans carry some Neanderthal DNA, only about 5% have Denisovan genes. Villanea and co-lead author David Peede examined genomes from individuals in Mexico, Peru, Puerto Rico, and Colombia, asking where the Denisovan MUC19 variant was most common. The answer pointed to the Americas, with roughly one in three people of Mexican ancestry carrying a copy of the variant.

The team discovered that the Denisovan segment is embedded within a larger stretch of Neanderthal-derived DNA. Villanea likens this to an Oreo, “with a Denisovan center and Neanderthal cookies.” This finding marks the first clear case of Denisovan DNA reaching humans through Neanderthals, rather than direct Denisovan-human mixing.

Adapting to New Worlds

After humans reached the Americas, natural selection seems to have favored the Denisovan MUC19 variant. The first Americans encountered environments vastly different from those of their ancestors, facing new pathogens, foods, seasons, and terrains. A mucus-related gene that improved barrier defenses or mucosal health may have provided a significant advantage.

Villanea notes, “All of a sudden, people had to find new ways to hunt, new ways to farm, and they developed really cool technology in response to those challenges.” Over 20,000 years, their bodies were also adapting at a biological level.

The Future of Ancient Genes

The migration story of early humans spans ice, coastlines, and time, illustrating a journey from a shared ancestral population around the Bering Strait into a continent rich with diverse biomes. “What Indigenous American populations did was really incredible,” Villanea said. Genes like MUC19 offer a record of that adaptation, capturing how ancient encounters with cousins like Denisovans left tools that descendants later used.

The research team now aims to test how different versions of MUC19 function in living people. Does the Denisovan variant alter mucus properties in the mouth, gut, or airways? Could it change infection risk or inflammation? These questions could connect a striking evolutionary story to present-day health.

For now, the lesson is broad. Human evolution is not a straight line but a braided river with tributaries from Neanderthals and Denisovans. Some of these tributaries carried genes that proved crucial when humans ventured into new worlds. The first Americans adapted with ingenuity, culture, and technology—and, as this study reveals, with a little help from ancient DNA.

The study is published in the journal Science.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates. Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.